Commemorating Darwin: Global Perspectives on Evolutionary Science, Religion and Politics

By Joel Barnes and Ian Hesketh

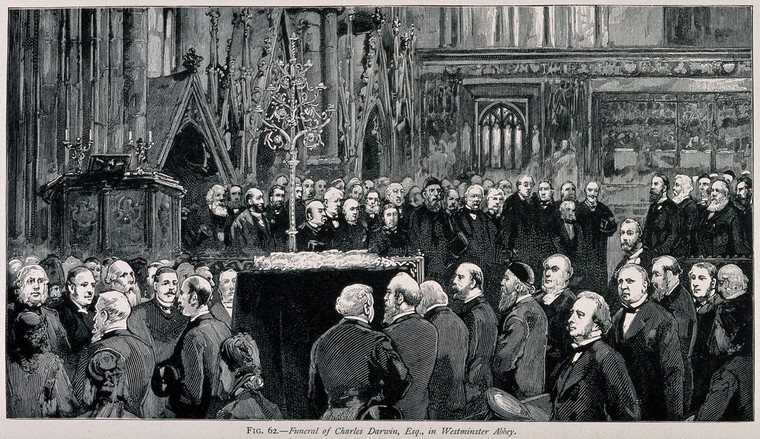

By the time Charles Darwin died on 19 April 1882, he had become a scientific celebrity, widely known for his studies of evolution that many believed transformed the way humans understood themselves in relation to the natural world. Since then his memory, and his celebrity, have been reshaped and rewritten many times over in different social, scientific, religious and political settings. We have had Darwin the secular saint, Darwin the national icon, Darwin the genius of rare insight, Darwin the model of patient scientific empiricism, Darwin the reckless purveyor of unevidenced abstractions, Darwin the harbinger of godless materialism, Darwin the political radical, and Darwin the ideologue of laissez-faire, among many others.

Many of these Darwins have taken shape in moments of memorialisation and commemoration, beginning with his death and burial in Westminster Abbey, and continuing through landmark anniversaries. The celebrations, at 50-year intervals, of Darwin’s birth in 1809 and of the 1859 publication of On the Origin of Species (1909, 1959, 2009) have been key moments of Darwinian reimagining. So too have anniversaries of the publication of The Descent of Man (1871), of the Beagle voyage, and of Darwin’s death. Since 1959, such commemorations have generated much of what we now think of as the ‘Darwin Industry’. Otherwise, in many settings moments of would-be memorialisation have been used less to reflect on the actual history of evolutionary science, than to advance political, religious and scientific agendas in their respective presents.

Our current project, funded by the INSBS, examines Darwin’s memorial afterlife in a global frame. The project brings together contributors across five continents, examining Darwinian commemorations across Britain, North America, Latin America, Asia and Australia. We are currently working towards an edited collection (under contract with the University of Pittsburgh Press) that will begin with chapters examining memorialising responses to Darwin’s death in several different national contexts, and continue through key jubilees in different settings throughout the twentieth century, and into the twenty-first century. The chronologically latest chapter brings us up to the 150th anniversary of The Descent of Man, which was marked in 2021. Considering such activities across the span of some fourteen decades since Darwin’s death highlights generic similarities between end-of-life memorialising genres such as eulogies and obituaries, and commemorations of later jubilees such as centenaries.

A special point of focus, the subject of a group of chapters situated in Australian, Canadian and US contexts, is the Darwin centenary of 1959. In a now-classic article on the 1959 Darwin Centennial at the University of Chicago, Vassiliki Betty Smocovitis argued that events there—the largest Darwin celebrations of that year—were less about the ‘historical Darwin’ and more about the public legitimation and consolidation of the modern evolutionary synthesis, that is, the fusion of Darwinian natural selection and Mendelian genetic theory that had developed in the biological sciences over the previous several decades. Chapters in the volume will revisit the Chicago Centennial a generation on, setting this alongside examinations of that moment elsewhere in the world.

Considered in a broad transnational and long-term frame, contributions to the project collectively bring out the remarkably protean nature of the Darwinian legacy, the ways in which Darwin’s character, his science, his religious views, and his relations to questions of politics, nationhood and race have constantly been rewritten by each generation. Sometimes such rewriting has been in response to the emergence of new sources. The publication, for instance, of The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin (1887), Darwin’s unexpurgated Autobiography (1958), and his notebooks (from 1960) each changed how different aspects of his life and career were understood. As often though, a Darwin was created to suit the times, given the different religious, scientific and political contexts in which Darwinian commemorations—and in some cases resistance to them—occurred.

Together the chapters show the variability of science-religion relations in different settings, and the interactions of both with local and national political contexts. They raise questions too of the relations between science and the history of science, of our roles as historians of science (and as historians of histories of science!) in the nexus between contemporary science, religion and politics. We’re looking forward to bringing the volume to fruition soon!

Joel Barnes is a historian with interests in histories of evolutionary science, the humanities, and universities, based in the School of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry at the University of Queensland, Brisbane. As well as his work on the Darwin commemoration project, he was Postdoctoral Research Fellow on the history strand of the INSBS-supported Science and Religion: Exploring the Spectrum of Global Perspectives project, which investigated the complexity of historical and contemporary relations between evolutionary science and belief across a number of national settings.volume, Nation, Nationalism and the Public Sphere.

Ian Hesketh is Associate Professor of History in the School of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry at the University of Queensland, Brisbane. His research focuses on the relationship between history, science, and religion in the modern period. His recent publications include A History of Big History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023) and the edited volume Imagining the Darwinian Revolution: Historical Narratives of Evolution from the Nineteenth Century to the Present (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2022).