Science, Spiritualism, Stereoscopy: The Spectacular Photographs of ‘Margery’ Crandon

By Dr. Emma Merkling

In late 2022 I began working on an INSBS-funded grant project on the scientific testing of the spiritualist medium Mina ‘Margery’ Crandon in Boston, c. 1925. ‘Margery’ was arguably the best-known medium in America at the time, having been made famous by a series of investigations into her mediumship initially funded by the popular magazine Scientific American. These investigations were conducted in Margery’s Boston home by an international group of physicians, physicists, psychical researchers, theologians, and stage magicians (among others) seeking to establish the genuineness of the strange phenomena she manifested in the darkness of the séance room.

These phenomena included a range of spectacular ‘physical’ effects, from levitating tables to the production of ‘ectoplasm’: a strange, tangible substance understood by spiritualists to be the physical manifestation of ‘spirit’ itself, which seemingly emanated from Margery’s orifices during trance states. During séances, her hands held by her physician husband Dr Le Roi Goddard Crandon on the one hand and her investigators on the other, Margery would slip under the ‘control’ of an entity identified as the spirit of her dead brother Walter, whose hoarse, disembodied whisper commanded proceedings.

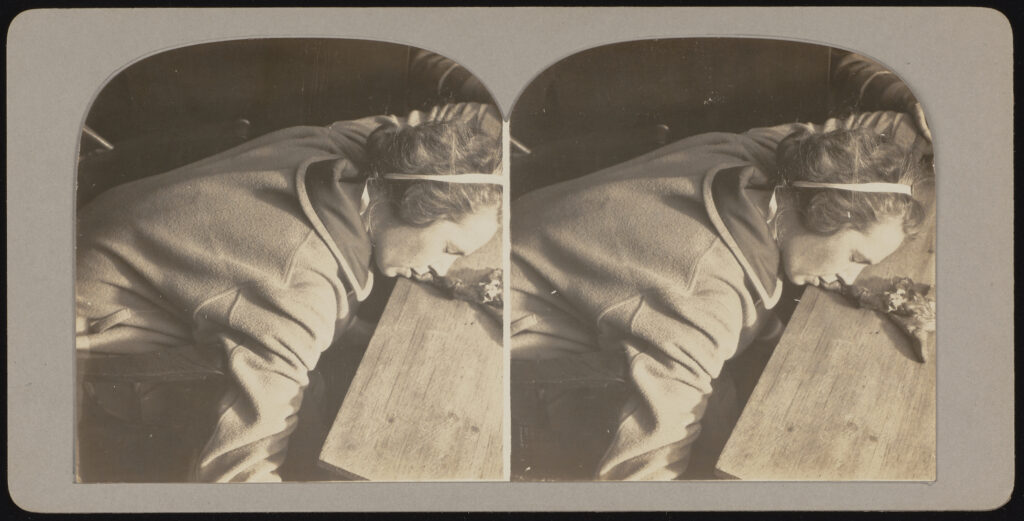

A stereographic photograph of ‘Margery’ Crandon exuding ‘ectoplasm’ during a test séance (1925). Image courtesy of Society for Psychical Research / Cambridge University Library (MS SPR/39/15).

My focus is on the strange and beautiful stereographic photographs taken during these séances. These photographs, scattered across various archives in the UK, US, and Europe, depict Margery’s body in the throes of spectacular ectoplasmic manifestation. Stereographs are early forms of 3D media which, when viewed with a special device called a stereoscope, exploit our natural binocular vision to enable two apparently ‘flat’ 2D images to ‘merge’ in our visual field. We then experience these images as volumetric — that is, in three dimensions. These volumetric properties are well-suited for capturing the tangible, dimensional stuff of ectoplasm. They seem to bring the strange substance physically — palpably — into the realm of our own experience: the space and place of here and now.

For this reason, looking at these photographs through a stereoscope is a thoroughly immersive experience — and also, I find, a curiously personal one. As I press my eyes to the viewer, blocking out the world around me, Margery’s body — twisting and turning as the strange fleshy substance emerges from her nose, or mouth, or navel — comes into focus. The experience is at once marvellous and uncanny. Textures are heightened, from the silkiness of her robe to the rubbery folds of the ectoplasmic substance; her skin and soft hair seem to glow and I feel I can almost reach out and touch her — and her ectoplasm. With their sharp clarity, seemingly random framing, and stark, flashlit quality, the photographs of Margery speak in the visual language of scientific imaging. But the process of viewing these photographs engenders feelings more commonly associated with entertainment — enthrallment, titillation, morbid curiosity — and even religious experiences — awe, amazement, wonder.

What I am interested in is the use and role of this particular form of media in the scientific investigation of Margery’s ‘supernormal’ body, and what it can tell us about the function of spectacle and performance at work in the séance room — especially as these relate to the scientific study of spiritualism. Why were these stereographic photographs produced, and how were they used? What did these media technologies do for their makers and audiences? And what can this tell us about the scientific study of the extraordinary? My entry point into these questions is a set of art-historical tools and approaches which offer new insights into some of these questions. These include: situating the visual register of these images within the lineage of scientific photography on which they so clearly draw; uncovering their conditions of production; establishing where and how they were displayed and recovering the experience of viewing them; and delving into the media histories which underlie them.

Digging into these aspects took me down routes I was not expecting. For one thing, I came into this project expecting the whole case to hinge on questions about Margery’s investigators — about their scientific validation practices, the challenges of empirical observation, and the virtue epistemes underlying their programmes of research. (You can see some of this thinking — and hear more about the Crandon case — in a talk I delivered as part of this project last November.) But looking more closely at the objects and the conditions of their creation has redirected my attention towards the spiritualist team at the heart of the whole process — Margery Crandon, her husband Dr Le Roi, and the ‘spirit’ Walter, who were directing the whole show.

Stereoscopy is interesting in the Margery case partly because of this media’s hybrid history as a tool of scientific demonstration and a form of popular entertainment. Like the scientific investigation of the supernormal, it has always belonged to the realms of both the empirical and the spectacular. Delving into the documents surrounding the Crandon case, it becomes clear that the stereographic photographs of Margery worked for their makers and audiences precisely because they mobilised these aspects of wonder and titillation through the visual language of scientific empiricism and evidence. This was as true for the spiritualists as for the investigators, and indeed we find stereographic photographs of Margery put to spectacular use in spiritualist contexts as well as in more conventionally ‘scientific’ ones.

As I come to write up the article based on my research, and thus close out this particular project, I’m pursuing a line of thinking in which the key to this case — including teasing out the knot of science and belief at its heart — lies not so much in questions of the scientific practices of its investigators, as in questions of the processes of spectacle, entertainment, and performance mobilised by spiritualists and investigators alike. As an art historian, I’ve found this shift in focus remarkably and personally rewarding, further confirmation of the value of art-historical tools and methods in studying science and belief in context. Looking closely at stereoscopy in the Crandon case unlocks something important about the processes outlined above, and why they might have worked — both in terms of the production of spiritualistic effects, and in the production of scientific ones.

Dr. Emma Merkling is a nineteenth- and early twentieth-century art historian with a focus on women artists, alternative science, spiritualism, and occultism. Emma currently serves as Deputy Associate Director of Research at Durham University’s Centre for Nineteenth-Century Studies International; and the 2023 Paul Mellon Centre Rome Fellow at the British School at Rome. Emma also hosts the podcast Drawing Blood, exploring visual culture, the history of science and medicine, and the macabre. The podcast can be found in all the usual places, and you can learn more about Emma’s work at https://emmamerkling.com/.