Religious Belief and the Geohistory of the Planet: Between Orthodoxy and Heterodoxy

By Richard Fallon

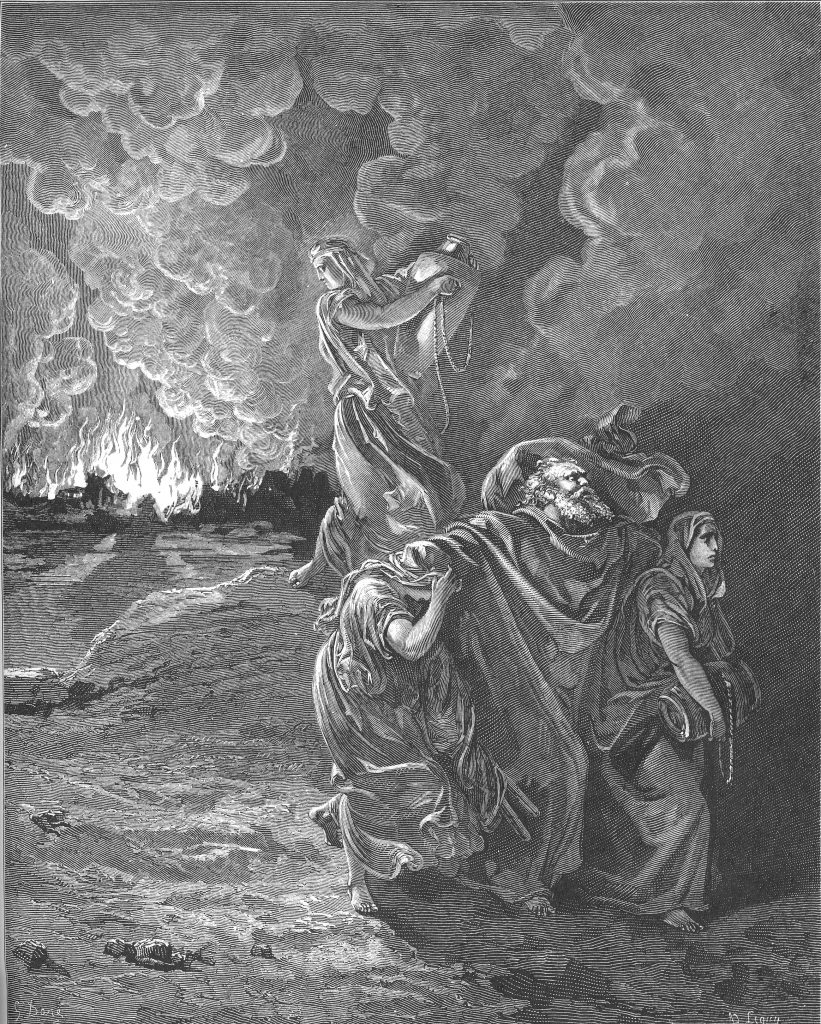

In September 2021, Nature-affiliated journal Scientific Reports published a striking article arguing that the Bronze Age city of Tall el-Hammam was destroyed by a cosmic airburst. The authors, Ted E. Bunch et al, speculated that the Genesis story of the destruction of Sodom preserves memories of this impact – and received intense criticism in response. Just a few months later, scholars in Geology described another suggestive episode in the geologically recent past, citing remains in the Atacama Desert in Chile to propose that a comet struck the area around 12,000 years ago. Curious, no?

Despite the significant differences between these two articles, connoisseurs of scientific controversy, and of the historical relationship between religion and the earth sciences, will recognise both as the latest iterations of a long tradition in which geoscientific research has appeared, or been construed as appearing, to conform with momentous events in religious and mythological history. Bunch and co’s Sodom angle is a twist on the more usual point of interest: that vast nexus of Flood catastrophism at which meet the likes of Noah, Gilgamesh, Vaivasvata Manu, and the denizens of Atlantis.

Given the typically defiant outsider stance of, say, young-earth Christian creationists, it may be surprising to see technical scientific journals publish claims that reflect on fabled catastrophes with seeming positivity. Last century, Immanuel Velikovsky’s book Worlds in Collision (1950), which used vast quantities of comparative religious data to argue for a devastating cosmic impact about 1500 BCE, came to epitomise the kinds of fringe stances excluded from mainstream science. Postwar scientists raced to characterise Velikovsky, a Hebrew scholar and psychiatrist, as a pseudoscientist, and to sever his association with the scholarly publisher Macmillan.

As historians and philosophers of science know, the demarcation term ‘pseudoscience’, fraught enough at the best of times, is wholly useless at describing many historical conjunctions of geoscientific research and religious belief. In the early decades of the nineteenth century, for instance, leading savants like William Buckland linked their geological work to the Biblical Flood; at the century’s end, John William Dawson and James Dwight Dana, two of North America’s most eminent geologists, continued to insist that Genesis accurately described the planet’s history. Despite the immense bodies of scholarship on ‘Genesis and geology’ and the global reception of evolutionary theory, much remains to be understood about how the scientific reinforcement of scriptural history played out as the earth sciences slowly and unevenly specialised and institutionalised. If the religious beliefs of practicing scientists were increasingly ‘privatised’ out of scientific literature in Europe and America by the close of the nineteenth century, as Ronald Numbers argues, the operations of those scientists who did not (and do not) keep their Christianity out of their geoscience present fascinating case studies. As for the incorporation of geoscience into the reinforcement or naturalisation of religions other than Christianity, vast scope for research remains.

These issues sit prominently among the several themes of a special issue of Interdisciplinary Science Reviews which I am editing alongside Edward Guimont. In ‘Conceptualizing Heterodox Palaeoscience’, which focuses on the period from the eighteenth century to the present, we hope to bring together not just historians of science and religion but also scientists, literary scholars, sociologists, and philosophers. We want to understand the negotiation of scientific orthodoxy in a field with a history of non- and interdisciplinary nebulosity and spectacular paradigm shifts; a field that broadly converted in the nineteenth century from creationism to evolutionism, for instance, and from continental stabilism to continental drift in the twentieth. As the influential reinvention of young-earth Flood Geology suggests, control of this ever-developing geohistorical narrative has often been a point of intense importance for religious conservatives and fundamentalists. Accordingly, we are seeking a more intimate understanding of how control of the narrative has been sought at diverse levels of society and at different historical moments.

The recent Scientific Reports paper raises interesting questions about the extent to which scientifically-minded believers have employed or rejected the prevailing naturalism of mainstream geoscience to validate events from religious lore. For one, how might we compare the craggy late nineteenth-century disciplinary climate in which evangelical geologists like Dawson uneasily worked, on the one hand, with faith’s place in the more firmly areligious professional geoscience of the postwar period, on the other? These matters are not, of course, restricted to the journals and institutions that have come to signify scientific legitimacy. When access to these spaces has been refused (or has not been sought), what strategies are pursued? In the wider public sphere, where the mechanisms of scientific publication can be more readily challenged, how have would-be palaeoscientists employed alternative funding and publishing routes, institutions, methodologies, argumentation, and genres to establish their religiously-inflected visions of earth’s deep history?

These are just some of the topics we will be thinking about in our ISR special issue, which also explores other forms of heterodox palaeoscientific belief that overlap with religion in complex ways, from cryptozoology and adventure fiction to flat-earth theory. You can find more information about the issue and how to submit in on our call for abstracts, the deadline for which is 6 May 2022, with papers due in March 2023.

Richard Fallon is a Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellow in the Department of English Literature at the University of Birmingham. His current research project is entitled ‘Borderline Geoscience and Transatlantic Literature in the Age of Lost Worlds’.