A Look at the Professional Creationists and Anti-Creationists

By Ted Davis

***This post originally appeared on 22 October 2015, on Ted Davis’ blog, Reading the Book of Nature hosted on the BioLogos website***

Evolution and Religion: The Conflict Narrative in Crisis

Recent results of the social scientific research on creationism in the United States raise more questions than they answer, especially with respect to long-held assumptions of what creationism actually is and what motivates people who affirm it. For instance, one of the most frequently-quoted polls on creationism is Gallup’s long-running survey that asks whether people believe that “God created human beings pretty much in their present form at one time within the last 10,000 years or so.” The percentage of Americans who answer in the affirmative ranges at around 45%, a number that has proven rather stable over the years. Social science has employed several methods to get beyond the layer of fact-claims established by this kind of polling and laid bare a range of moral and social motives that are at the core of people’s reasons for identifying as creationists.

Recently, research sponsored by BioLogos contributed to what I consider a fruitful shattering of long-held assumptions when Jonathan Hill’s National Study of Religion and Human Origins showed (among other things) that for many Americans it is not even important if they are correct on things like the date of creation or the means by which God created humans. Surprisingly, then, the question is no longer why such a large section of the American population stubbornly clings to a long-refuted explanatory framework—in reality there aren’t very many Americans who are fully convinced of the YEC view. Most are not very sure about what they believe, they don’t see their beliefs primarily as a means of explaining the world in a scientific sense of the term, and often they do not think it is very important to be right about the seeming core elements of creationism. Thus, the question becomes why—in public debates and in much of the social scientific research—is creationism still treated as if so many of its adherents really do exhibit these characteristics?

Why is it Important to Look at Professional Creationism?

One part of the complex answer to this question lies in an analysis of the things professional creationist organizations do and the resources they possess. In the United States, a relatively small number of institutions such as Answers in Genesis (Petersburg, KY), the Institute for Creation Research (Dallas, TX), and the Center for Science and Culture (Seattle, WA), constitute what one could call the public face of creationism. They are important organizations to examine when one tries to make sense of the state of science-and-religion discussions in general and, more specifically, the dynamics of the creation/evolution debates. First, they serve as key producers of knowledge, arguments, and strategies. Well-known slogans and labels like “creation science,” “intelligent design,” “teach the controversy,” the idea of “millions of years,” and many others are being disseminated by these small groups of professionals. What’s more, they also provide numerous sources that enable non-professional creationists to engage with their ideas. If there is something like a creationist culture (or counterculture), the output of these organizations, from books to summer camps, does a great deal to create and maintain it.

As might be expected, this has a big impact on how creationism is perceived by the wider public. For example, Answers in Genesis presents its views as an integrated system of theological, social-moral, and scientific considerations with frequent links between these areas. The fact that their view is rather prominent—and is expected to become even more so once their life-sized ark is finished—partly explains why creationism is regarded as a system of thought rather than merely a disparate set of sometimes-believed hunches.

It’s not hard to see how this skewed view enters social scientific research. When pollsters ask themselves what questions they could ask in order to find out the spread of creationist views among the public, they often follow the order of relevance that is set by the professional creationist organizations and resort to what they regard as the key tenets of creationist thought systems. By doing so, they reinforce the impression that what actually counts for “creationists” is to be right about theories of creation.

This does not mean that professional creationists do not have any “real” influence on perceptions of creationism. On the contrary, creationist legislative, educational, and media efforts have often proven so big a threat to scientific establishment in the United States that a coalition of scientists, educators, and secularists formed what I would describe as an anti-creationist organization. In order to understand how creationism works it is important to understand how their professional opponents work.

Anti-Creationists Mirror their Opponents

A closer look at professional anti-creationist organizations such as the National Center for Science Education (Oakland, CA) reveals that they match their creationist opponents in many respects. They lobby political support to fend off creationist legislative advances in states like Kansas and Tennessee, they produce educational material that explains and refutes the core claims of creationism while recounting the history of their organizations, and they point to alternative ways of combining science and religion that do not (in their opinion) harm either—such as Theistic Evolutionism. In any case the NCSE makes clear that accepting evolution by no means implies or presupposes atheism.

However, not all engaged in countering creationism in the United States agree with that claim. There is another faction that I would call the anti-theistic anti-creationists, who build their cause around a refutation of core religious claims using what they regard as scientific means. There is a significant split between both camps, with anti-theists accusing the NCSE of being “accommodationist” to religious claims and the NCSE making sure not to identify with any particular worldview so as not to lose the credibility of a neutral defender of science.

Mirroring the Mirror

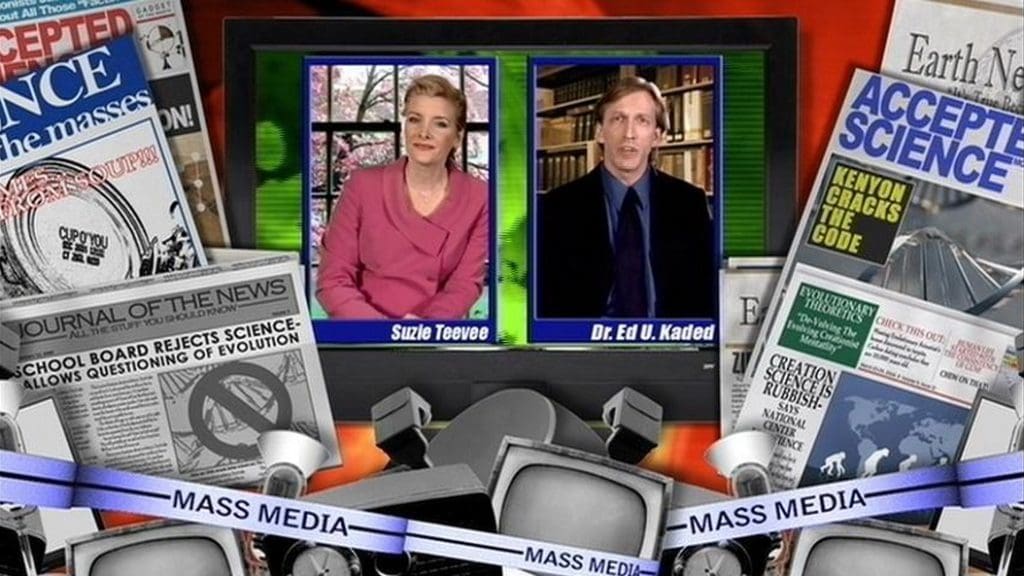

There exists a constant feedback loop between the creationists and their opponents. Anti-creationists, of course, orient themselves toward their opponents, in order to counter their influence as efficiently as possible. Creationist organizations like Answers in Genesis, on the other hand, perceive this opposition and follow it very closely. The extent to which this orientation has become a habit for leading creationists sometimes pops up for the keen observer (such as this PhD student of the workings of US creationism) in certain details of their actions. Consider this screenshot of a video from Answers in Genesis at the top of the page that shows how they see popular secular media as skewed toward secularism and against their cause. In the frame, very subtly and partly concealed, the National Center for Science Education is featured as one of the supposedly anti-religion groups. What makes this reference so interesting is precisely that it is so subtle and en passant.

The extent to which professional creationism and anti-creationism are attuned to one another goes beyond this micro-level. Considering the strategies professional creationists employ, one can distinguish between overtly religious creationist organizations like Answers in Genesis and groups that push for more subtle forms of creationism that omit overt references to religion, such as the Center for Science and Culture—the leading Intelligent Design think tank. The already-mentioned split within the anti-creationist camp mirrors this structure: whereas the NCSE deliberately refrains from linking their defense of evolution with a worldview critical of religion, other anti-creationist actors do just that, especially the New Atheists, who make their case for the religious non-neutrality of evolution and science.

It is possible to trace these current differentiations to a common source. When in the 1980s scientific creationism was losing important court battles, a number of people involved in that movement reframed their message to conceal religious aspects of their ideas even further. This resulted in what today is called Intelligent Design. During these years, anti-creationists struggled to bundle their resources for an effective counter-initiative to scientific creationism. They could not advocate for any particular religious or political position in order (among other reasons) not to lose their tax benefits. This development led to today’s NCSE. At the same time, the leading creationist organization of that day, the ICR, instituted a new ministry called Back to Genesis, paving the way for the overtly biblical creationism that today is successfully represented by Answers in Genesis. On the other hand, vocal anti-religious scientists like Richard Dawkins have tended to make creationism a prime target of their ire whenever it was on the upswing in the United States and other places, and they mention the theories and activities of their creationist counterparts frequently. So the neutral-overt distinction in creationist strategies is also found in anti-creationism.

Toward a Sociological Reassessment of the Creation/Evolution Controversy

When looking at creationism as a play of a small number of specialized elite actors, several things become visible that otherwise would not. For instance, it can be said that creationism in this sense is neither only an extension of the religious field in the United States, nor is it just a struggle at the margins of science. In a way, it is both and neither. The actors all employ scientific and religious expertise, but they don’t do it to advance in either of those fields. (As a matter of fact, to argue for the religious compatibility of their scientific or “scientific” views might even harm them in the scientific field.) They might aim for a change in how science works, like the Center for Science and Culture, but they mainly revolve around the continuation of what they already have: an established position among a group of specialists that are neither only religious nor only scientific actors but that frequently employ the language and expertise of both.

This way of talking might be one of the reasons why professional creationism keeps going in the United States, and it can be used as a means to describe and even define creationism. It can be said that the ground rule for everyone who participates in the debates about creationism is never to talk just about religion or just about science, but always to synthesize the two directly or indirectly in various ways. One can go further. Sidestepping the laden notions of science and religion, one can say that the common object of all professional creationists and anti-creationists is to put forward specific answers to the question, what parts do God and nature play in explaining the world? (The world in this sense consists of “everything that is the case” as Wittgenstein put it, including feelings, the soul, and religion and science themselves.) Creationism as presented by the professional creationists and in public discourse can then be defined as a way of talking about God and nature that ascribes God a relatively large role in explaining the world and nature a relatively small role.

Defining creationism like that shifts the focus in a helpful way, since it is being de-essentialized and characterized as a process that always already involves other positions. This process is shaped by the outcome of past rhetorical and legal battles and by the various sources of cultural, social, and economic capital of the professional creationists and anti-creationists alike.

Conclusion

When looking at this complex and highly specialized field of professional creationist and anti-creationist organizations, one can find at least part of an answer to the question why public talk about creationism seems so detached from social scientific findings about it. Their success in representing creationism or anti-creationism is only in part dependent upon being identical with what their constituencies think. Rather, they are oriented toward each other, the legal and cultural frameworks within which they act, and the expectations of mass media and professional science journalism. They are largely autonomous regarding their finances and trademark slogans, and they have an interest to continue to exist as institutions. Social scientific research about creationism is only beginning to take this differentiation between an elite discourse and the everyday representation of “creationism” more seriously.

Edward B (Ted) Davis is Distinguished Professor of the History of Science at Messiah University and Fellow of the International Society for Science & Religion. For more see his Research Profile.