Is the Danish Minister of Higher Education and Science a creationist? – The monkey business revisited

By Hans Henrik Hjermitslev

During July and August 2015 the Danish public witnessed a heated controversy on science and religion in the popular media. The reason for this was that two historians of religion, Michael Rothstein and Jens-André Herbener, accused the newly appointed Minister of Higher Education and Science, the Liberal MP Esben Lunde Larsen, of being a creationist and therefore unsuitable for the office.

Experts, including myself, were eager to defend Larsen in the press. However, the controversy revealed serious misconceptions of human evolution, modern Protestant theology and the relationship between science and religion among religious scholars and journalists, who often subscribe to a simplistic conflict narrative.

Herbener and Rothstein, who are known for their anti-Christian agenda, made their accusations in the nationwide leftist newspaper Politiken on 7 July. They were based on Larsen’s comments on the origin of the universe and mankind, when interviewed on the occasion of his appointment as minister. Larsen was asked whether he believed that “human beings descend from apes” and answered that he believed that “a creating God is behind it all”, but that theology did not provide an answer to the question of evolution. According to Larsen, both theology and biology offered suitable answers to the origin of the universe and no conflict existed between science and religion.

These statements made Herbener and Rothstein conclude that Larsen was a creationist who supported a literal reading of scripture and rejected modern science. They also regarded Larsen’s separation model of science and religion as untenable. According to the two historians of religion a necessary conflict existed between religion and science. Their article was accompanied by a flood of comments on social media where the appointment of Larsen was called “a Joke”, “a scandal” and “an insult to science”.

The controversy reached the pages of all major newspapers in Denmark. A large number of experts on science and religion, such as theologians, sociologists, historians and philosophers, were interviewed in the press. The vast majority of them, including myself and one of my co-editors of Creationism in Europe the director of the National History Museum of Denmark Peter C. Kjærgaard, made it clear that the minister’s views had very little to do with any kind of creationism and that he implicitly distanced himself from creationism by arguing for a separation model of science and religion, which is mainstream among theologians at universities and clergymen in the national Evangelical-Lutheran Church, where biblical literalism and creationist views are marginalised. As I emphasised, Larsen, who holds a PhD in Theology, belongs to an influential faction of the church inspired by the national icon N.F.S. Grundtvig (1783-1872) whose so-called church view asserts the priority of the Apostolic Creed and the sacraments to scripture. Generally, Grundtvigians accept the theory of evolution and distance themselves from creationism and biblical literalism. In fact, Larsen’s own research focuses on Grundtvig and his influence.

In order to clarify matters and calm down the critique, Larsen was interviewed by the science news site videnskab.dk and visited two popular television shows hosted by the public Danish Broadcasting Corporation (DR). Larsen made it clear that he was not a creationist and that he supported scientific research that contradicted a literal reading of scripture. He also emphasised that science and religion were two different language games that had to be separated.

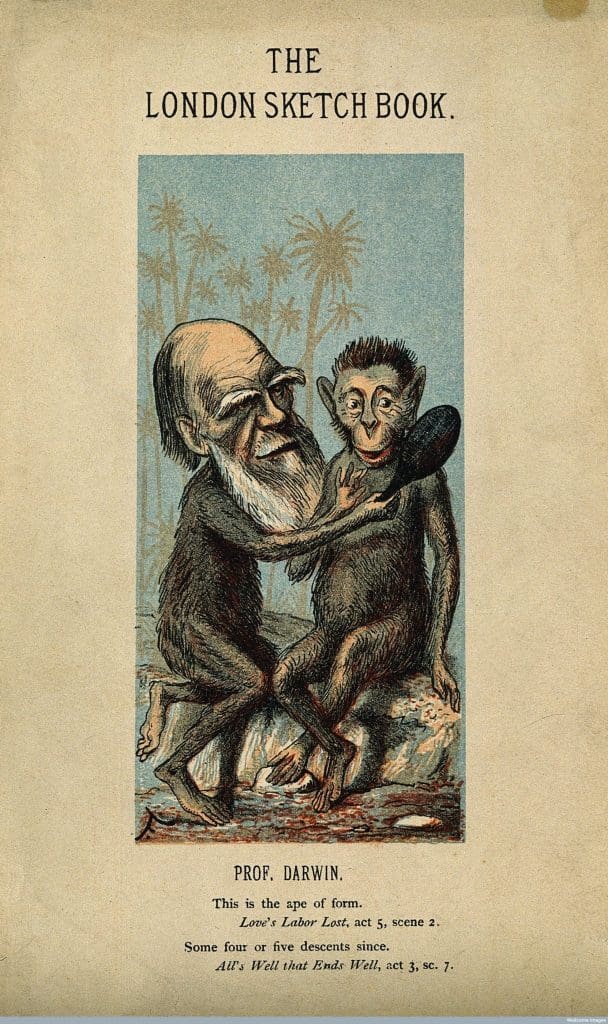

In one of the television shows Larsen was asked by the journalist to choose between a picture of Adam and Eve and photo of a chimpanzee. This illuminates my argument that the controversy revealed misconceptions of human evolution as well as Christianity among journalists. In the case of human evolution the popular myth that human beings descend from living apes was reproduced. While, in the case of Christianity, journalists – and even historians of religion – tended to equate religious faith and biblical literalism and thereby reproduce the conflict thesis of science and religion, which has been widely criticised by scholars for decades. For journalists it creates an exciting narrative to describe science and religion as two antagonistic powers fighting each other from the beginning to the end of days.

This inaccurate narrative influences the general public, whose knowledge of modern Protestant theology is rather limited even though 79 percent of the Danish population are members of the national church. Despite the strong support for the church as a cultural institution, Denmark is a highly secularised country: as we have documented in Creationism in Europe, only 19 percent of Danes think religion is important to their daily life, 2 percent attend Sunday service on a regular basis and 31 percent believe in God, while more than 83 percent of the population accept human evolution.

The simplistic conception of religion in the Larsen case echoed one of my earlier experiences with science and religion in the media. During the widespread celebration of the bicentenary of Charles Darwin’s birth in 2009, a group of researchers at Aarhus University including Kjærgaard and myself launched a variety of science communication and public engagement initiatives including the website evolution.dk in order to strengthen scientific literacy. However, we soon realised that the greatest challenge was to explain to journalists, pupils and students that the conflict narrative of science and religion – that is Darwin versus God – was untenable. So we were faced with religious rather than scientific illiteracy.

Thus, the challenge for scholars of science and religion is twofold. On the one hand, we have to engage the public in the debate about creationism, which is central to our understanding of what constitutes proper science. On the other hand, we have to reach out to journalists, school teachers, students and even religious scholars and explain that Protestant theology does not necessarily harbour any creationist and fundamentalist claims and that believing in God as the creator does not mean interpreting the biblical history of creation literally.

Hans Henrik Hjermitslev is a historian of science and religion and an assistant professor at University College South Denmark.

Hans Henrik Hjermitslev is a historian of science and religion and an assistant professor at University College South Denmark.