How Does the Science-Religion Conflict Narrative Affect Christians?

By Kimberley Rios

This article was originally published on the Heterodox Blog and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution, Non-Commercial, No-Derivatives 4.0 International License.

Just a few weeks ago, a blog post appeared in my social media news feed titled “Why your Christian friends and family members are so easily fooled by conspiracy theories.” The post caught my eye not just because of its controversial title, but also because its central message – that Christians should avoid spreading and endorsing misinformation – resonated with my research on negative stereotypes about Christians in science.

Indeed, the notion that science is incompatible with religion (particularly Christianity) prevails in many Western societies. The 2009 appointment of Francis Collins, a self-identified evangelical Christian, as director of the National Institutes of Health was fraught with controversy, and Harvard professor and popular science author Steven Pinker continually makes headlines for arguing that religion has no place in intellectual or scientific reasoning. The science-religion conflict narrative extends beyond these well-known examples. Research in social psychology has shown that North Americans evaluate God less positively after reading about strong (versus weak) scientific theories; in other words, they tend to see scientific and religious concepts as polar opposites.

Whether science and Christianity necessarily do conflict is not the focus of my work. Rather, I examine how Christians themselves respond to societal perceptions of a fundamental clash between science and their religion – specifically, how and why such perceptions affect Christians’ performance in science. In a recent set of studies, I examined two possibilities. First, Christians might see the conflict narrative as reinforcing what they already believe – that science does not comport with their cherished values. This possibility is embodied in the title of the blog post I mentioned earlier and suggests that Christians simply are not motivated to excel at science in the first place.

A second, alternative possibility is that Christians do care about science and see the conflict narrative as detrimental to others’ perceptions of their group. Similar to the aforementioned cautionary note that sharing misinformation “makes Christians look like idiots,” Christians may be concerned that the conflict narrative confirms stereotypes about their group’s investment in science, rather than endorsing the narrative themselves. They may therefore underperform on scientific tasks due to the pressure they feel from such concerns.

Participants in one study, all American adults recruited from an online platform, were randomly assigned to one of two groups. The first group read a purportedly real news article called “AAAS [American Association for the Advancement of Science] Speaks Out on the Perceived Incompatibility Between Religion and Science,” which claimed that most Americans believed Christianity and science are in conflict, and that most scientists do not believe in God. The second group read an article called “AAAS Speaks Out on the Perceived Compatibility Between Religion and Science,” which made the mirror opposite claims.

Participants then completed a task described as a measure of scientific reasoning ability. The task consisted of fifteen nonsense syllogisms – two statements plus a conclusion – and participants had to decide whether each conclusion reflected good or poor reasoning. An example is, “No cats are electrified. All ghosts are electrified. Therefore, no ghost is a cat.” This task is accessible to participants regardless of their scientific background, unlike, say, a chemistry test that requires prior knowledge of particular content. I recorded the number of correct solutions, as well as how much time each participant spent on the study (minus time spent reading the news article). I also had participants indicate their agreement with four statements about stereotypes of their group’s scientific abilities, such as “I worry that people’s evaluations of my scientific ability will be affected by my religion.”

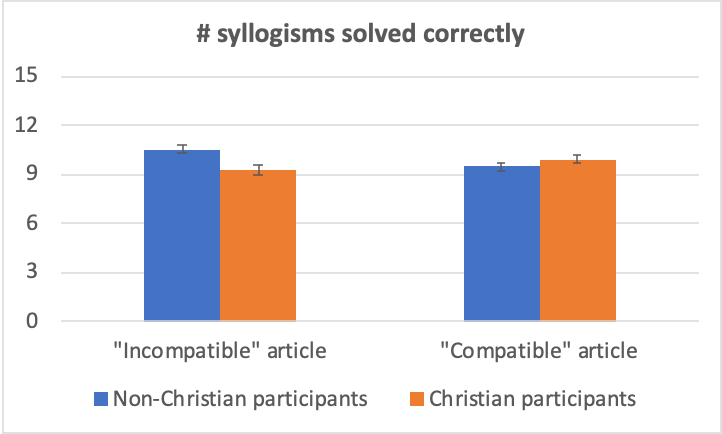

Among those who read the “Christianity and science are incompatible” article that reinforced the conflict narrative, Christian participants solved fewer syllogisms correctly than did non-Christian participants. However, among those who read the “Christianity and science are compatible” article that dispelled the conflict narrative, Christian and non-Christian participants performed similarly.

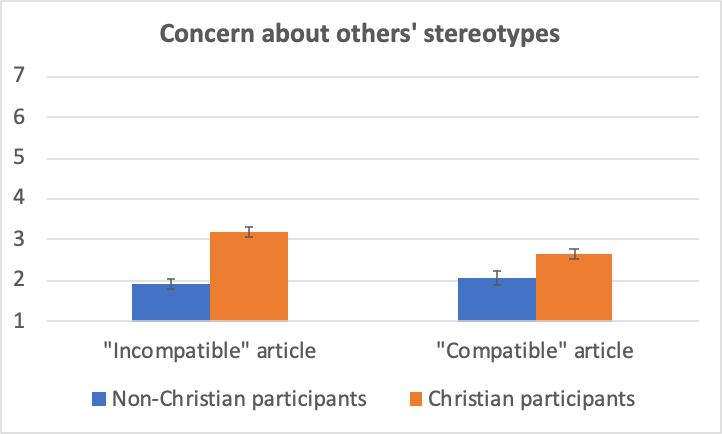

Why, though, did Christians suffer a decrement in performance after being reminded of the religion-science conflict narrative, but not when this narrative was rebuked? Two findings in this study support the possibility that Christians feel pressure to disprove negative stereotypes about their group’s aptitude in science. First, Christians who read the “incompatible” article reported being more concerned with others’ perceptions of their scientific abilities, compared to both non-Christians and Christians who read the “compatible” article. If they lacked investment in science, they would not have reported such concerns. Second, Christians who read the “incompatibility” article spent about the same amount of time on the study than did their non-Christian counterparts. If Christians had simply disengaged from (i.e., “blown off”) the scientific reasoning task after reading the “incompatible” article, they would have spent less time on the study.

Notably, in two follow-up studies, the religion-science conflict narrative impacted Christians’ scientific task performance the most among participants who reported being highly engaged with science (i.e., among those who would most want to belong in science). This again refutes the argument that Christians in my studies were predisposed to dismiss science as inconsistent with their beliefs. If that had been the case, my effects would have been strongest among participants who were not engaged with science to begin with. For these participants, the “incompatible” article would have underscored their initial notion that science was “not for them,” hence making them unmotivated to perform well on the task.

These results by no means demonstrate that Christianity and science are always compatible, or that Christians and non-Christians are equally invested in science across the board. Instead, they suggest that many Christians are invested in science. Too often, the potential for Christian and scientific identities to coexist gets lost in the conflict narrative that pervades many Western cultures. But my studies found that Christians performed as well as non-Christians on scientific tasks when Christianity and science were described as compatible. What’s more, Christians felt anxious about others’ perceptions that their religion does not mesh with science.

Why should this research matter to those who do not identify as Christian or even religious? For one, the vast majority of Americans believe in God, and most are Christians. Given that U.S. students’ science literacy lags behind that of their peers in other developed countries, and over 25% of American adults think the sun revolves around the Earth, narratives that hamper the scientific performance of such a large segment of the population are problematic. Additionally, diversity in beliefs and values can improve decision-making in groups and organizations. Debunking negative stereotypes about the religion-science relationship (e.g., by highlighting the accomplishments of exemplars like Francis Collins) may encourage individuals with different religious and spiritual beliefs to pursue science, which may increase diversity in scientific fields. Perhaps, then, we should be asking not why Christians reject science in favor of conspiracy theories, but rather what the barriers are to Christians’ participation in science and how educational institutions and the general public alike can address these barriers.

Kimberley Rios is an Associate Professor of Psychology at Ohio University. Her research explores the causes and consequences of stereotyping/prejudice among religious majorities and minorities, both within the U.S. and cross-culturally.

For more see Kim’s Research Profile, or check out her website.